This content is provided by Sabin Metal Corporation and reflects their views, opinions, and insights.

A trend has emerged in the petroleum and petrochemical refining industry over the past five years or so as an ever-increasing percentage of carbon is being found within alumina and silica-alumina precious metals (PM) catalysts sent in for reclaim. Some of the material arriving is over 40% carbon, and this has been corroborated by many PM refining companies around the world. This high-carbon trend is creating processing backlogs for precious metals refiners, which is resulting in long delays in metal returns to catalyst owners. This article hopes to raise awareness in petroleum and petrochemical leadership teams, and open further dialog between the catalyst owners and precious metals refiners to find and implement solutions to this dilemma.

It is unclear whether this high-carbon trend is a result of less and less in-situ pre-reclaim burning to save time/money on turnarounds, longer process run times, or simply more difficult feedstocks. The most likely answer is that it is a combination of all of these factors. The decision to delay maintenance and turnarounds during the COVID crisis has been quite common, but this high carbon issue pre-dates COVID. The issues of feedstock choice and the analysis of run-time lengths being far more technically motivated decisions, we will instead focus for the moment on the bottom line that we must all somehow address: the removal of the carbon.

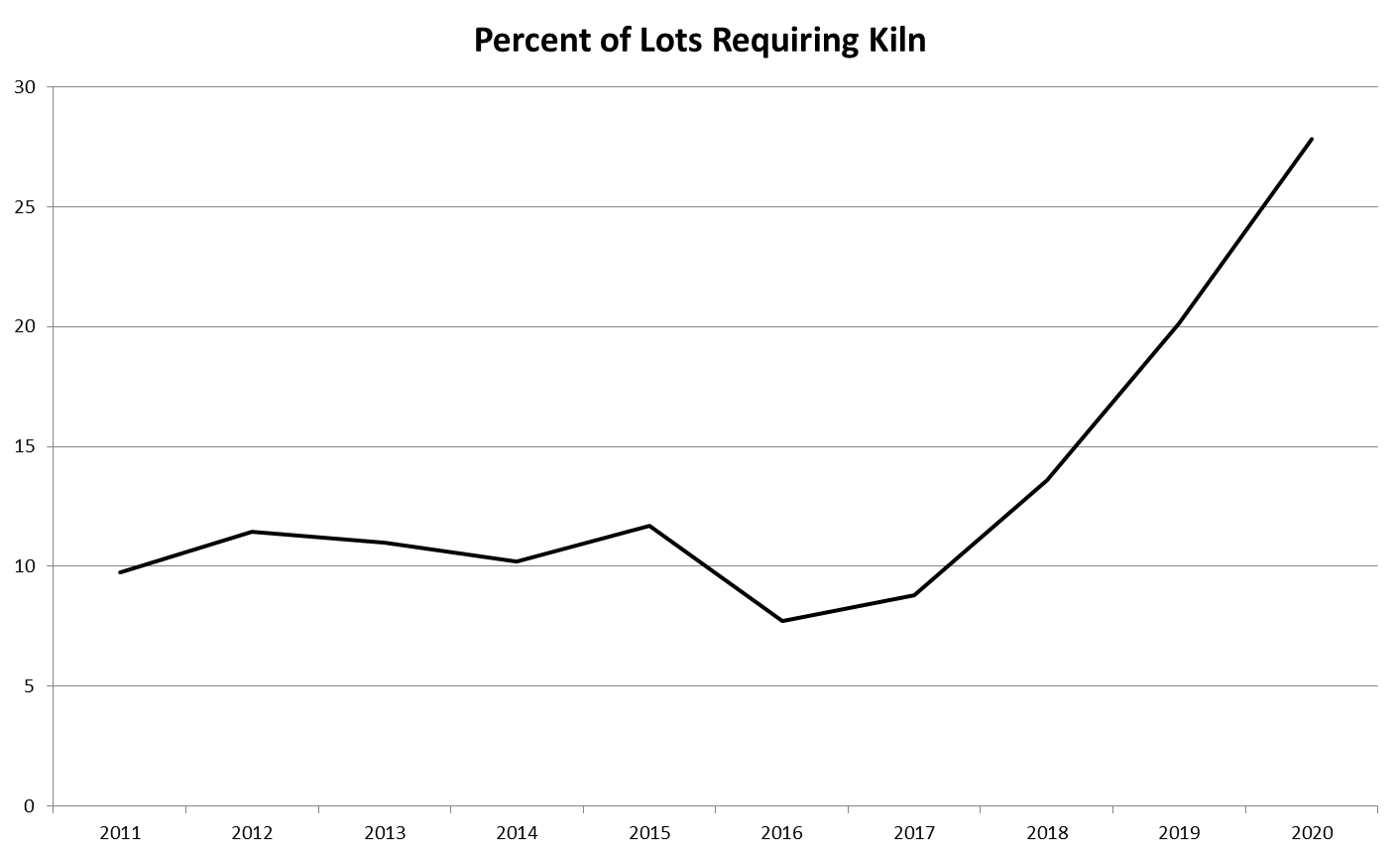

Not that long ago, pre-reclaim kilning was standard operating procedure for just about every precious metals catalyst change out; now it is much more common to dump the used cat and send it out to the PM reclaimers dirty. While we do not have detailed data from our competitors, the increase in carbon-loaded lots shipped to Sabin (those that must be kilned) looks like this:

Remaining at or around 10% for at least six years prior to 2011, the rise to the present day is dramatic and clear: three times more carbon and coke than just a few years ago.

In-situ pre-burn and the perception of cost savings

Two petroleum customers have provided pre-reclaim burn cost case studies from units with different catalyst types. Although both case studies used essentially the same timeline, for discussion purposes we have rounded the in-situ regen time up to an even 24 hours. Each unit in the study contained 200K lbs. of catalyst, but different products were being made, so the revenue per day varied—and therefore so did the cost:

$550K revenue per day reactor = in-situ burn at $2.75 per lb

$945K revenue per day reactor = in-situ burn at $4.73 per lb

Average: $3.74 per lb.

We could get ourselves into anti-trust thin ice if we start talking about how much all the various precious metals reclaimers charge for kilning, but suffice it to say that it is way less than $3.74 per pound. It would certainly appear from the front-end view that outsourcing the carbon removal is cost-saving, as it allows a faster refinery return to production. This has led many catalyst users to choose to forego the in-situ burn, drop the dirty cat and send it off for kilning at a much lower rate. These high levels of coke, carbon, and other contaminants are creating significantly higher operating costs for the reclaimers, not to mention storage issues, etc.

Why kilning?

Basic sampling theory rightly stresses homogeneity, so there is no getting around the necessity of kilning. The contamination levels within the catalyst, whether they are carbon, moisture, etc. must be eliminated or greatly reduced to make it possible to properly sample. Inaccurate sampling would result in erroneous precious metal content calculations—which is, of course, very bad for everyone. Additionally, both hydro- and pyrometallurgical precious metals recovery methods require low-carbon feed for best precious metals recoveries and overall efficiency.

Reclaimers are doing what they can to handle this growing need for excessive kilning. The construction of Sabin’s third kiln is complete in North Dakota, and theoretically this will eliminate approximately one-third of our backlog. The problem is that the dirty stuff just keeps coming; and now the repercussions are being felt by the catalyst owners and the PM marketplace.

The carbon negatives

Increased wait times for final precious metals return

- Catalysts that are received clean, that is, with carbon, benzene, moisture, etc. all within acceptable tolerances, can proceed directly to sampling. The typical settlement time for these relatively clean materials (that is, from receipt at the reclaimer facility to final delivery of the precious metal value to the client) is generally three to four months. This includes all processing, laboratory analysis of the samples, and final paperwork agreement and execution. These so-called “clean” catalysts may have come from a product line that does not generate carbon, benzene, etc., or they may have been burned in situ (the pre-reclaim burn) or sent out for burn at a specialized vendor before shipping to the precious metals reclaimer.

- The settlement time when kilning is required is at least twice that long. In some extreme cases, heavily coked catalysts (over 40% or so) require second or third runs through the kilns to reduce the carbon sufficiently. This timeframe includes waiting their turn in line for kilning and the kilning time itself.

- Are you leasing platinum or palladium? Lease rates on Pt are currently around 3.5%; lease rates on Pd? Well, I’m only half joking when I say that there is no lease rate on Pd—because no one has any. Standard platinum content of 0.3% means that leasing costs can exceed $1000 per day. It is not unusual for some catalyst owners to spend closer to $2000 per day on lease fees. In either case it closes the perceived savings gap by a significant amount.

“Trapped” precious metals

- If a PM reclaimer has a backlog at the kilning pinch-point, all of the material waiting in line is just sitting in the warehouse. All of the platinum group metal (PGM) ounces contained have been removed from circulation for the length of the backlog.

- Double trouble in the PGM market: the silicon carbide and tungsten added to automotive catalyst recycling has created similar issues. Specialized processing is now necessary, there are only a few places that can mitigate the “contaminants,” and an untold number of PGM ounces remain trapped in inventories waiting their turn.

- China has effectively closed its export of any PGM catalysts, in what can only be called protectionists movements in the last few years. Over 80% of purified terephthalic acid (PTA) production is in China, to name just one market example.

- And lastly, the details of the mining industry cannot be ignored. PGM comes from South Africa and Russia almost exclusively, the ore quality is deteriorating, it is getting more expensive to pull each ounce out of the ground, and demand isn’t going down.

Possible solutions and conclusions

There would appear to be a limited number of possible corrective actions:

- Solution: The PGM reclaimers have to add more kiln capacity.

This is ongoing but will not achieve full correction and will almost certainly mean higher pricing. - Solution: Catalyst owners must calculate the full cost of skipping the in-situ burn and start making this process the norm again.

When company savings only show up within a single area of responsibility, and the future repercussions are somewhat clouded, these types of decisions would have to come from a higher level of management. - Solution: If the PGM reclaimers raise their kilning prices to near or the same level as the cost of in-situ pre-reclaim burning, the catalysts users will re-evaluate shipping the cat dirty.

This should have the desired effect over time, but customers who do not understand the factors contained herein are likely going to see red and seek services elsewhere. Competition is always encouraged, as long as it can be done on a level playing field. In precious metals the cheapest option is never the right one and will certainly not remain the cheapest in the final analysis—but we must save that topic for another time and place.

A greater sharing of information between catalyst users and precious metal refiners will help immensely to gain greater understanding of this problem. We encourage readers to get involved in this kind of industry stewardship and look forward to working together to achieve a “win-win.”

Disclosure: This content is provided by Sabin Metal Corporation and reflects their views, opinions, and insights.

Bradford Michael Cook

Brad joined Sabin Metal Corporation in late 2012 and was named Vice President of Sales and Marketing in January 2015. He has over 35 years’ experience in the precious metals industry in numerous roles. Brad has been a member of the International Precious Metals Institute since 1999, currently serves on its Board of Directors, and was the President of the Institute for the 2012–2013 term.