Selling residential rooftop solar is a tough slog. Total system costs are still too high, which includes the costs of finding and persuading homeowners to plop a big, new structure on their roof. That leaves a small window for CEO course corrections. So choosing either a bad technology or a bad business model can be fatal. Dow Chemical, a slow-moving $63 billion behemoth, managed to make both mistakes.

On the other hand, at SolarCity Elon Musk, the man, the myth, the promotion machine, chose a better technology, while agilely adapting the company's business model to changes in the market. Unfortunately many reporters haven't acknowledged the importance of that difference.

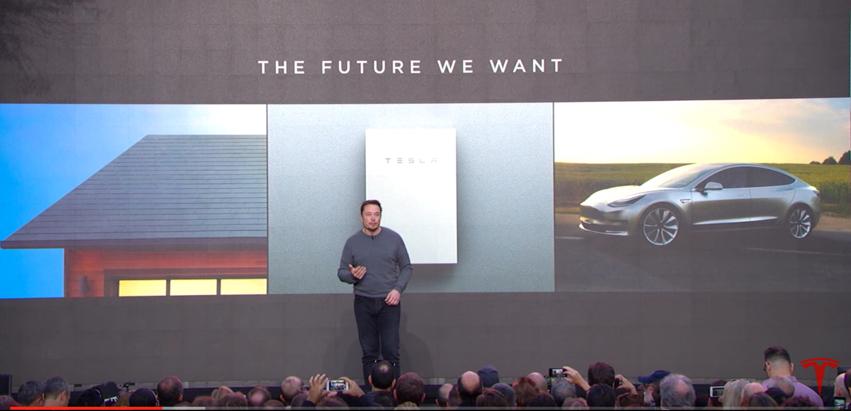

Cognitive dissonance flared up last October when Musk, showing off the synergy of the pending Tesla/SolarCity merger, live-streamed the unveiling of his company's new solar roof to a global audience. Containing embedded solar cells, the indestructible glass Tuscan or faux slate tiles cover a home's entire roof. That's a departure from the solar installer's rack-mounted panels and opens up a smaller, second revenue stream from upscale customers barricaded inside gated communities.

Afterwards many reporters quickly predicted possible failure. Negative articles pointed to Dow Chemical's recently discontinued Powerhouse solar shingles to explain their verdict.

Dow's brilliant idea

There are many reasons Tesla/SolarCity's solar roof might not catch on, but it's important to realize that Tesla, a nimble startup fronted by Musk's megawatt personality, doesn't have Dow's problems to worry about.

Dow's problems began in 2010 — with a treacherously brilliant idea. Company execs looking to cash in on the solar boom had watched the market expand from early adopters to the general public, and, even more enticing, they also knew that asphalt shingles cover four out of five homes in the US. Suddenly it was a no-brainer to integrate small clusters of solar shingles into all of those roofs.

At the time, Jane Palmieri, managing director of solar solutions for Dow, said, "We foresee a potential addressable market of $5 billion by 2015."

During Dow's splashy 2011 launch, CEO Andrew Liveris thought his new solar shingles were a slam dunk, confidently telling reporters that the technology was "...a key part of its strategy to invent and innovate."

Unfortunately, Dow's early decision doomed its project from the start. Since asphalt shingles are the cheapest roofing material on the market, Dow stayed in the same niche by using inexpensive thin-film CIGS [copper indium gallium selenide] cells, which, at the time, were much cheaper than silicon. But there was a catch: CIGS cells were less efficient. So when prices for silicon modules started dropping, finally falling 80% over the next five years, Dow's cost advantage was wiped out, and reduced efficiency became a big liability.

Having passed up silicon for a newer technology, Dow also had a hard time scaling up production to reduce costs. Reportedly, output stumbled along at only 400 shingles a day for a long time. Eventually Dow's customers realized that buying building-integrated solar (BIPV) from Dow amounted to "paying a premium for less return," as Greentech Media's Julian Spector said at the time.

So although owners could take advantage of net metering paybacks facilitated by Dow's grid-connected inverters, the returns were disappointing.

On top of that, why embed a system when a rack mount makes repairs and solar upgrades so much easier? There's another advantage: since asphalt roofs absorb a lot of heat and jack up air conditioning bills, rack-mounted solar reduces energy costs by insulating the roof from the sun.

So even though Dow worked hard to increase its shingle's power density, improve the appearance and speed up production and installation, less than five years after their debut, Liveris had Dow pull the plug and stop the assembly lines.

Elon Musk's special brand

Dow's business model backfired too. Conventional silicon-based solar is already complex, but anyone thinking of buying Dow's new CIGS solar shingles needed even more information, which should have been tied directly to the company's scientific expertise.

Instead Dow used its normal sales channels and signed deals with builders, who then sold the shingles to homeowners. In a market flooded with solar installers, Dow's shingles sank to the level of a generic commodity.

As the anti-Dow, nothing Musk does is remotely generic. At his latest rollout, after he introduced Tesla's elegant solar roofs, he lured new customers with an updated Powerwall 2.

By the end of the presentation, he'd connected electric cars, solar roofs, and storage batteries into an integrated clean-energy company — all built upon Musk's highly branded one-stop shop, where consumers can ask questions and take test rides as they sort through the technologies.

Bloomberg reported that Musk has said, "You have an integrated solar roof with a Powerwall and an electric car, and you just go into a Tesla store, just say yes, it just happens. It all works, it’s seamless and you love it."

Tesla already has hundreds of retail locations around the world, with some getting between 3 and 4 million walk-ins a year. This will significantly reduce SolarCity’s customer acquisition cost, which currently represents almost $1 per watt installed. Recently Tesla has said that by adding a new store every four days this year about 440 stores will open worldwide by the end of 2017.

The electricity is just a bonus

Once the solar gigafactory in New York is working at capacity, Musk thinks the company can get solar cell costs to 40 cents per watt, which is competitive with current commodity solar panels. Unlike Dow's shingles, the Tesla solar panel is 22% to 24% efficient, which is a big improvement over commodity solar panels converting 10% to 15% of light into electricity.

Perhaps the most surprising Musk factoid is that Tesla’s new solar roof will actually cost less to manufacture and install than a traditional roof — even before savings from the power bill. “Electricity,” Musk said, “is just a bonus.”

Tesla also wants to bring battery packs down to about $100 per kWh by 2020. At that price, a Tesla Powerwall battery could cost as little as $640 to manufacture. With the synergy created by an integrated Tesla/Solar City, the costs of bundling a battery with a typical $25,000 rooftop solar system would be easily absorbed. So it becomes — from Musk's point of view — a must for Tesla to provide batteries with every new solar installation.

Tesla's future energy platform

“Musk’s intentions are larger than simply adding a third product category,” BNEF analyst Hugh Bromley told Bloomberg. “The future of Tesla Energy could be in energy services.”

By producing the cheapest lithium ion batteries on the market, and offering them with every rooftop solar system it sells, eventually Tesla will control of a large supply of battery storage. While sharing the proceeds with customers, Tesla will sell energy back to the grid when demand is greatest.

This will provide the grid with extra capacity during peak demand, while also smoothing out the tiny surges and shortfalls of the electricity supply.

Frequency control is considered "the most popular service for stationary storage,” said BNEF analyst Julia Atwood. “And it pays well because the provider has to respond incredibly quickly and accurately.”

How quickly can Musk pull off his energy services dream?

Images: YouTube screen grabs