This article is a collaboration between Cory Jensen and Elizabeth Horahan

You may not have heard of the Donora Death Fog, but if you are interested in climate change, you should have. This notorious weather event is arguably one of the most pivotal moments responsible for the adoption of air quality regulations in the United States. Though more of a "Smog" than a "Fog," this aptly named phenomenon left 20 dead and half a town hospitalized in its wake during the fall of 1948. It showed all of the characteristics of an atmospheric inversion, an event in which air stops circulating and is trapped close to the ground. The combination of trapped toxic gasses and early morning mists yielded disastrous effects.

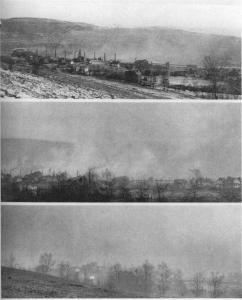

In the early morning hours of October 26, 1948, a fog settled over the town of Donora, Pennsylvania, the home of U.S. Steel Corporation's Donora Zinc Works and American Steel and Wire. As the day wore on, the fog became progressively thicker and witnesses even claimed that it was so thick and potent they could taste it. By October 29, the inversion had trapped so much pollution and fog that attendees of a local high school football game noted that they couldn't even see the players on the field. Doctors ordered the elderly and those having trouble breathing to leave town, which became impossible as visibility was reduced to nothing - firefighters had to abandon attempts to deliver oxygen to suffering citizens as they were unable to navigate the town--in the middle of the day. On the morning of October 30, the two U.S. Steel plants ceased operation. The following morning the fog had begun to dissipate leaving many surviving residents with permanent respiratory damage.

Collusion of weather and pollution

So what combination of factors led to the Donora Death Fog? Further, what long-term effects and impact did this combined weather and man-made catastrophe have on our country?

Early on October 26, an anticyclone traded places with a regular East Coast storm over Western Pennsylvania. An anticyclone is exactly what you think--the opposite of a cyclone. Instead of a concentrated low-pressure system, an anticyclone can cover large areas and consists of a high pressure system which draws air down through the system and out in a clockwise motion. This natural phenomena itself does not commonly result in death. When combined with the geographic location and industrial nature of Donora, the ensuing unnatural weather occurrence wreaked havoc on the town's air-based mass balances.

Located 37 miles south of Pittsburgh, Donora is nestled in the Monongahela River Valley. In the valley, the cool ground contributed to a strong temperature inversion. Under normal conditions, the air close to the planet's surface is warmest and decreases in temperature with increasing altitude. The warm air at the surface begins to rise replaced by cooler air that is then warmed by the sun hitting the Earth's surface. That warmed air rises and causes constant air flows. During a temperature inversion, however, the cool air gets stuck at the surface. The early morning fog in the valley was created when the cool front and high pressure system interacted with moisture in the air, which reflected and blocked the sun's ability to warm the cool air at the surface of the Earth. With little air movement, the pollution emitted by the steel-belt town had nowhere to go but into the valley, increasing in concentration. Particulates like zinc, cadmium and lead emitted by the plants contributed to the sun-blocking, compounding the problem and ensuring a stagnant layer of air.

The now poisonous air contained more than just particulates--it also contained hydrofluoric acid, sulfur dioxide, and carbon monoxide. In a news clip published in Chemical and Engineering News on December 13, 1948, it was revealed that the victims of the smog experienced acute fluorine poisoning determined by the extreme fluorine levels in the blood of the deceased (12 to 25 times the normal levels) and the near-asthmatic breathing of the survivors. Humans were not the only victims--all of the crops in the area perished. Corn, which is highly sensitive to fluorine exposure, was especially devastated.

"Death Fog" leads to modern anti-pollution laws

Donora was not the only recorded temperature inversion with a death toll. In 1930 in the Meuse River Valley area of Belgium, 63 people perished; in 1950, 22 people died in Poza Rica, Mexico; and in 1952, the infamous London Fog claimed 4,000 lives over the course of 5 days. Los Angeles smog was clearly apparent in the 1940s, leading to California passing their first state pollution law in 1947. The Federal Government later followed suit in 1955 with the Air Pollution Control Act. This act, however, did not attempt to authorize the government to control pollution (that would follow later in 1963 with the Clean Air Act) but did allocate federal funds toward research on air pollution. Though Pennsylvania had been passing laws protecting the water supply since 1905, the first act concerning air pollution was put into law in 1959 when Pennsylvania passed legislation to afford the state the authority to prevent the "pollution of the air by smokes, dusts, fumes, gases, odors, mists, vapors, pollens and similar matter, or any combination thereof."

Since that time an Executive Order by President Nixon created the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, which was tasked with enforcing air pollution laws. That includes laws enacted by the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1970 which, among other things, authorized vehicle emissions standards.

The tagline at the Donora Smog Museum is "Clean Air Started Here," denoting that their suffering played a big part in opening the eyes of Americans to the hazards of air pollution and spurred political action that has carried forth through today and will continue into the future. On this day, the 63rd anniversary of the Donora Death Fog, let's all take a deep breath and be glad that we can.

Special thanks to the Donora Smog Museum, the Donora Historical Society, and the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources program at California University of Pennsylvania for use of their Donora Digital Collection.

Comments

Great article. It is sad that it takes events like this for people to understand the benefits of clean air and water. Even sadder how quickly they are forgotten and people start to fight against the very rules that are protecting them.

What is that saying... history repeats itself? Hopefully not in this case, but to your point... people forget...

This was a great article! Thanks for all the hard work and research behind it. I grew up near Donora and had heard of the "death fog" when I was young, but I didn't know much about it, so thanks for the history lesson. The entire Monongahela Valley was once plagued by terrible air quality, including Pittsburgh, but for everyone attending next year's Annual Meeting in Pittsburgh, you'll see it has changed remarkably!

Thanks Douglas! I am hoping to swing by the Donora Smog Museum while I'm out at the Annual Meeting next year - I'd really like to see it!

We should organize this as a YP event, maybe incollaboration with the Environmental Division, IfS, SEF?

What an excellent idea!

Would you be willing to help out with such an activity?