Wind power in the US is poised to take off and provide almost as much electricity in 2050 as coal-fired power plants do today, according to an Obama administration report. The authors were comfortable extrapolating the recent tripling of wind power from 1.5% in 2008 to 4.5% in 2014, when hub height and rotor size increased dramatically. And one recent innovation assures that the trend will even accelerate.

MidAmerican Energy, Iowa’s largest utility, now says it's building the tallest land-based wind turbine in the nation from a common construction staple — concrete. Siemens is currently assembling the tower at a new wind farm in Adams County, Iowa, where instead of prefabing tubular steel and then trucking it out to the wind farm, local crews pour the concrete sections on-site, significantly reducing costs.

MidAmerican spokeswoman Ruth Comer said that the concrete turbine tower is already partially built. “All of our other wind turbines use a steel tower construction," she explained. The concrete towers are also more expensive than steel towers, but the extra cost will be offset by the turbine’s increased electricity production. (See the press release.)

100 extra feet

The turbine's tower will measure 377 feet from ground to hub, over 100 feet taller than traditional turbines. Measuring all the way to the highest blade tip, the 554-foot reach will make the wind turbine about as tall as the Washington Monument.

So why did steel fizzle? Industry standard tubular steel turbine towers are now built in three sections that total 250 to 300 feet, and transporting the long individual sections requires special trailers and logistics headaches. Low freeway underpasses, narrow railway crossings and tight tunnels usually limit the sections to 4.1-4.3 meter diameters, which, in turn reduces hub height to about 100 meters. If a developer decides to raise the hub to 120 meters, usually on a coastal site with easy access, the tower walls must be thickened, significantly increasing the cost.

Of course, changing from steel to concrete comes with tradeoffs: concrete contains cement, which is manufactured with serious carbon dioxide emissions. The cement industry already spews about five percent of total emissions. The steel industry also emits CO2, but it's not on the same level. So a global fleet of cement turbine towers would push cement's emmissions even higher.

While a steel tower has less environmental impact if a 20-year duration is calculated, concrete's longer life span can tilt the playing field.

That's because the deflection of a 300 foot steel tower is nearly three feet, while concrete, which is more rigid, will only bend about three inches. Concrete also minimizes the vibration that can punish equipment. So, ultimately, the combination of reduced deflection and lower vibration require fewer repairs or replacement. Developers can now extend a concrete-supported turbine's life to 40 years, making its impact much smaller.

An early adopter

Just to be clear, many concrete towers are already out in the international market. Acciona Windpower, for example, has a 3-megawatt turbine that can be installed using an 80-meter steel tower or a concrete version that can get as high as 120 meters.

Since Acciona's concrete towers were developed by the tunnel division of the parent company in Spain, which has extensive expertise building concrete structures on-site, Acciona has developed a highly sophisticated portable concrete batch plant that is brought in to pour the concrete sections locally.

The company has continued to refine the concept since first tower was installed over ten years ago.

46 concrete towers

Just recently, about 115km north east of Cape Town, South Africa, Acciona connected its 138MW Gouda wind facility to the grid. The 46-turbine wind farm, whose turbines have all been built with concrete towers, will generate about 400 gigawatt hours of electricity.

Acciona says that the locally constructed towers will have more impact on the South African economy than towers built with imported steel.

To date, Acciona has installed a total of 1,045.5 megawatts of concrete supported wind capacity around the world, shared between Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, Spain and Poland. The company has additional orders for more than 800 MW worldwide.

In addition to a new concrete tower production plant in Mexico producing 84-turbine towers in the state of Nuevo León, now Acciona has decided to introduce its concrete towers to the United States. According to Joe Baker, CEO of Acciona Windpower, the new technology will "allow us to bring more local jobs to the communities where wind projects are constructed."

Increasing regional reach

Acciona and MidAmerican are both counting on concrete wind turbines to open up profitable low-wind areas across the United States.

As the turbines get taller, they'll become viable in more regions, and more valuable in places where they are already deployed.

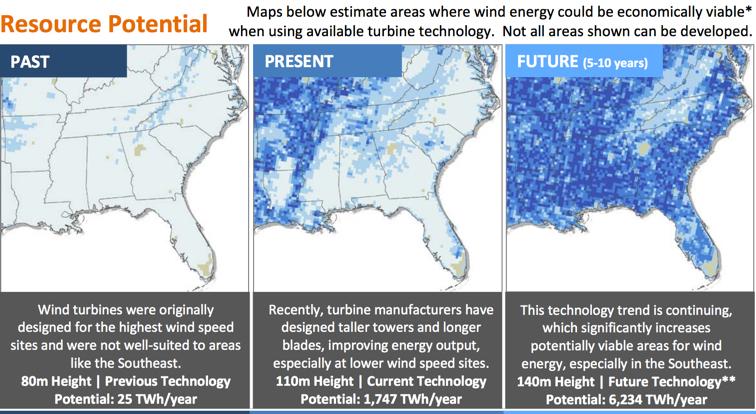

National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) wind maps show the impact of greater tower heights and improving turbine technology on wind's wider reach.

A previous generation of 80 meter hub heights led to a paltry 25 TWh of potential electricity production in the Southeast. But, with taller, 110 meter turbines more common in today’s installations, NREL estimated 1,747 TWh of annual electricity generation potential for the region.

At future heights of 140 meters, suddenly 6,234 TWh of electricity output is possible from turbines operating with 35% or higher capacity factors.

Will concrete turbine towers close the parity gap?

Images: Acciona Cape Town Turbines, Acciona; wind map, US DOE