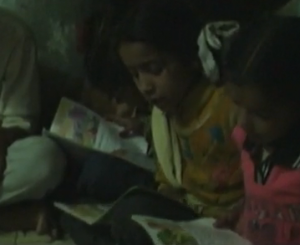

No country has more citizens living without power than India, where more than 400 million people have no electricity. Bihar, India's poorest state, has more than 80 million people living far away from the creaking power grid. On a moonless night in Bihar, everywhere you look is utter darkness-- except doorways framing the smokey glow from kerosene lanterns, where children struggle finishing homework before parents turn the light down, then out, to conserve fuel for the next night. The rural poor, living in extreme poverty, have been notified by the government that they will be waiting several karmic lifetimes for India's rural electrification program. While Consumer Reports considers that improved service, let's put it in perspective. Can you imagine waiting a lifetime at the DMV to get your license renewed-- in the dark? Too depressing? How about a week? Does the phrase, "When hell freezes over, then thaws, and freezes over, again!" clear things up? Since 2007, when Husk Power Systems electrified their first small village, the startup has quickly grown and now provides electricity for over 100,000 people across 125 of Bihar's villages, using only rice husk biomass feedstock. Ironically, this incredible accomplishment has barely begun to illuminate Bihar's night-vast darkness, but Husk Power is now that metaphorical lantern, slowly brightening.

Unlearning the Lessons of Los Angeles and New Delhi

Gyanesh Pandey, one of the company's founders, grew up in a village in Bihar without electricity.

"I felt low because of that," he told David Bornstein of the New York Times. He decided to study electrical engineering, eventually working for a semiconductor company in Los Angeles. While enjoying a sports-car-enabled bachelor's lifestyle, his job was to figure out how to get the best performance from integrated circuits at the lowest possible cost, which he now considers perfect training before eventually returning home and trying to bring electricity and light to Bihar.

Once Pandey had returned to India, he and Ratnesh Yadav, a childhood friend and one of the co-founders of Husk Power Systems, spent several years experimenting on high tech and cutting edge energy solutions. They tried making organic solar cells, and growing jatropha, whose seeds can be used for biodiesel. Impractical. Then they tested solar lamps. Limited. "In the back of my mind, I always thought there would be some high tech solution that would solve the problem," said Pandey. He just wasn't thinking big enough or low tech (DIY) enough-- blinded by science, still technologically stranded in the mega-cities of Los Angeles and New Delhi, and obviously, still very jet-lagged. In Bihar's small, rice belt farmer's villages, people waste very little. When the partners began to research living conditions, they found that even the garbage was used in some way. "Villagers have to live in complete harmony with nature," Yadav explained to Greenpeace. Eventually Pandey realized that in this impoverished countryside there was one substance going to waste: the leftover husks of milled rice grains. (The husks contained too much silica to be used for cooking fires.)

The millers even paid to have the husks hauled away to be burned or dumped and left to rot. So he decided to use this chaff to produce the electricity the villagers needed, and, in a sense, by using the Indian concept of "jugaad," which means finding a simple, effective and new solution, he had comfortably straddled both the new and old/new worlds. Techo-repatriation. How do I know? Pandey never once considered opening a nouvelle health food restaurant after sprinkling the crunchy husks over his morning granola. Before Pandey and Yadav could find the next important part of the solution, they had to run into a salesman who sold common gasifiers that burn organic materials to produce biogas. Gasifiers have been around for decades. They are very simple--completely the opposite of whiz bang high-tech. (It's like having a car salesman coax you out of that showroom Prius and into an old 57 Chevy at the back of the used car lot). But this was after the rice husk epiphany, and their defenses were down. Now the pieces to create Husk Power began to fall into place. "Nobody had thought to use rice husks to run a whole power system," explained Pandey. Pandey and Yadav quickly brought together a husk powered electric distribution system. They got a gasifier, and made changes to get it working right, by adjusting valves and pressures, pollution filters, and the gas-to-air ratios.

To bring down costs, they constantly simplified, removing everything non-essential. They even replaced automated features with hand cranks. Finally, they came up with a complete system that could burn 50 kilograms of rice husk per hour and produce 32 kilowatts of power, enough for about 500 village households.

They Reached Out to the People

To keep labor costs down they recruited locals, often from very poor families, and trained them to operate and load machines; and work as fee collectors and auditors, going door-to-door ensuring that villagers weren't using more electricity than they pay for. Wires ran from the modest power plants on cheap bamboo poles, carrying electricity to nearby houses to a maximum distance of two to three kilometres, because, beyond that, the voltage drops. Finally ready, they reached out to people in a village called Tamkuha, in Bihar, offering them an almost unbelievable deal: for 80 rupees a month -- roughly $1.75 -- a household could get daily power for one 30-watt or two 15-watt compact fluorescent light (CFL) bulbs and unlimited cell phone charging between 5:00 p.m and 11:00 p.m.

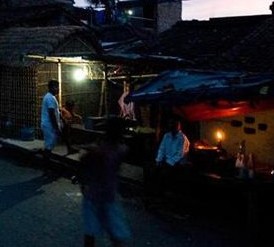

The price was less than half their monthly kerosene costs, and the light would be much brighter and less smoky. And the new customers could even pay for more power if they needed it. But many had no appliances and lived in huts so small, one bulb was enough. The system went live on August 15, 2007, the anniversary of India's independence. The following video was made by the Acumen Fund, a Husk Power Systems funder, to showcase the transformation of Tamkuha: The secret to their business model is that it's built on a feedstock that costs, as Yadav described it, "not that much." Since Husk Power pays under one rupee per kilogram for rice husk, the model seems unstoppable: this year, Bihar will produce 1.8 billion kilograms of rice husk. Focusing attention primarily on villages that are off-grid but setting up anywhere there is rice husk and a demand for electricity, to date, they have 35 power plants in operation; four at 52kW- and the rest 32kW-installed capacity. Once the 25 plants currently under installation are complete, Husk Power will have a total installed capacity of about 2MW.

Kids Can Now Study at Night

There have been many positive effects in the villages. Villagers say that burglaries have declined because of better lighting at night, and the number of snakebites in each village suddenly dropped to zero when the electricity came. Kids can study at home in the evening and now they have a better prospect for the future.

Quality of life for women improves because they can now see the insects that swarm as they're cooking, and shopkeepers make more money, able to stay open for more hours. Electricity to power one 30W CFL bulb costs 80 rupees a month, and most plants operate for six to seven hours every evening. "They wouldn't have got a better deal than this in their whole life," said Yadav. Husk Power has no interest in patenting their proprietary gasifier. The secret isn't the biomass gasification system, which is "so simple that even a person who cannot read and write can operate it with a little bit of training," says Ratnesh, but in their social blueprint, which builds an ecosystem around every plant where everyone benefits and growth becomes inevitable. At each step everyone makes profit. They purchase rice husk from local rice mills, which are earning more now. They collect Rs.40-50,000 (~$900-1,100) as revenue from the sale of electricity but give back Rs.10,0000/month ($222) to the villages in salary, rice husk, incense sticks, and bamboo.

And they even found ways to extract value from the rice husk char -- the waste product of a waste product -- by setting up another side business turning the char into incense sticks. This business now operates in five locations and provides supplemental income to 500 women. The company also receives government subsidies for renewable energy and is seeking Clean Development Mechanism benefits. Alone, none of these steps would have been significant. Taken together, however, they make it possible for power units to deliver tiny volumes of electricity while enjoying a 30 percent profit margin. The side businesses add another 20 percent to the bottom line. Pandey says new power units become profitable within 2 to 3 months of installation. He expects the company to be financially self-sustaining by June 2011.

A Collection of Small Old Ideas Well Integrated and Executed

Husk Power has identified at least 25,000 villages across Bihar and neighboring states in India's rice belt as appropriate for its model. Ramapati Kumar, an advisor on Climate and Energy for Greenpeace India, who has studied Husk Power, explained that the company's model could "go a long way in bringing light to 125,000 unelectrified villages in India," while reducing "the country's dependence on fossil fuels."

What the company illustrates is a different way to think about innovation -- one that is suitable for global problems that stem from poor people's lack of access to energy, water, housing and education. In many cases, success in these challenges hinges less on big new ideas than on collections of small old ideas well integrated and executed. "What's replicable isn't the distribution of electricity," said Pandey. "It's the whole process of how to take an old technology and apply it to local constraints. How to create a system out of the materials and labor that are readily available." Much of the information for this article came from a Greenpeace profile and a New York Times blog.

Do you prefer a bottom-up or top-down approach to energy fixes?

Photo- light in street- (C) Harikrishna Katragadda/Greenpeace Photos: Husks, gasifier, bamboo poles, reading- AcumenFund Photo: Ratnesh Yadav- (C) Harikrishna Katragadda/Greenpeace Photo: Women making incense sticks- Husk Power Systems screen grab Photo: Gyanesh Pandey- AcumenFund Photo: woman with lantern- (C) Harikrishna Katragadda/Greenpeace Photo: Gyanesh Pandey- Acumen Fund screenshot

Related articles

- A Light in India (opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com)

Comments

There is so much to be learned from this. Sometimes the greatest solutions come from ideas that are really very basic. Such an amazing story of using so little to create something something so useful!

we should all be so enterprising.

Kent, this was a really well put together piece on a DIY phenomenon that is happening all over India. A relative of mine works for the Acumen Fund and is also involved in education projects. Reading this really puts things into perspective when we complain that our Internet speeds aren't fast enough! Thanks for sharing with the ChEnected community.

This is the best example of what it means to be an engineer. And to think like an engineer. Someone's got to solve the world's apparently intractable problems. Someone, I think it was one of the founders of Sun MicroSystems, said that the 20th century was the era of the scientist, but the 21st century is the era of the engineer. The Acumen Fund sounds very farsighted. Internet? everyone was doing wi-fi on thew Bolt Bus today.